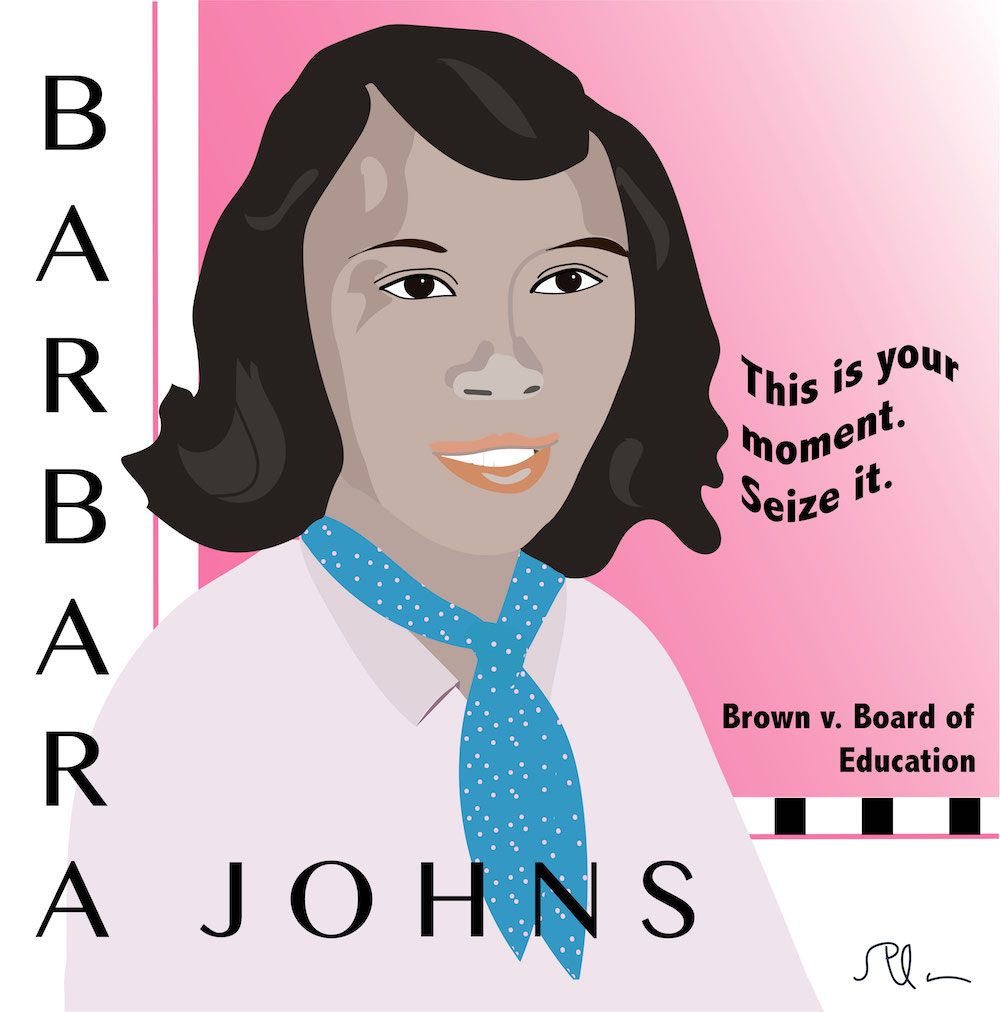

Barbara Johns: The Teen Who Started a Movement

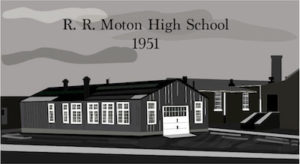

In 1951, Robert Russa Moton High School was a cluster of ramshackle buildings surrounded by dirt fields in Farmville, Virginia. The central brick building, which had been built in 1939 for the education of 180 black students, was far too small for the more than 450 students in attendance a dozen years later, so additional classes were held in tarpaper shacks erected on the campus.

When it rained, the roofs leaked. When it was cold, students seated far from the potbelly stoves would shiver. When it was hot, the buildings were stifling. Students had no gym for athletics, no lab for science, no cafeteria to eat lunch in. When they were sick, there was no infirmary to go to, and they had no lockers to keep their books in. Their teachers lacked a lounge or work room.

Farmville High School

But others in Farmville were having a different experience. Farmville High School offered the white kids in town an auditorium with built-in seats, a wood-floor gymnasium, an industrial arts shop, a teachers’ rest lounge, and a cafeteria. The multistory brick building was surrounded by lawns and trees and sidewalks, not dirt.

Barbara Johns was a sixteen-year-old junior who, with her family, had moved from New York to Farmville to live and work on her grandmother’s farm. Like her fellow students at Moton, Barbara noticed the discrepancies between the two schools. She was particularly struck by the unfairness one day when she was late for the always jam-packed Moton schoolbus. As she hitchhiked for a ride to school, the bus taken by the white kids to Farmville High passed by. It was only half full.

She complained that day about the bus and other conditions at Moton to her music teacher who challenged her to do something about it. So Barbara stewed about the issue for months and finally came up with a plan.

The Strike Begins

Barbara, accompanied by student body president Carrie Stokes and Carrie’s brother John, attended numerous school board meetings to request money for fixing up the school. But the school board kept deferring the matter. So, with the help of some upperclassmen and -women, Barbara implemented a more radical plan.

On April 23, she found a way to trick the principal into leaving the school: She made up a story about students downtown getting into trouble with the police. Then she wrote notes to the teachers about an all-school assembly to get the students gathered in one place. She was able to sign them with her own initials as they were identical to those of the principal. Once the auditorium was full, Barbara climbed onto the stage and tried to convince her fellow students to join her in a strike to protest the school’s conditions.

When she walked out of Moton that day, the students followed her. Johns later recalled that, at the time, she wasn’t afraid. All she thought was, “This is your moment. Seize it.”

For two weeks, the students continued their protest with no success. The superintendent of schools had no response other than to threaten the striking kids’ parents. So Barbara contacted the NAACP in Richmond.

Davis vs. County School Board

NAACP attorneys Oliver Hill and Spottswood Robinson III convinced the students to seek school integration from legal action rather than just improved facilities. Barbara agreed, and they filed a lawsuit, which bore the name of the first student listed as a plaintiff, Moton High’s 14-year-old Dorothy E. Davis.

The U.S. District Court ruled in favor of the school board the following spring.

Brown v. Board of Education

But the NAACP lawyers appealed, and in 1952 the case was taken up by the Supreme Court in conjunction with three additional school segregation cases from different states. Collectively they were known as Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka for Oliver Brown’s Kansas case filed on behalf of his daughter Linda, even though 75 percent of the plaintiffs were from Moton. The reason is that the Court did not want the case to be perceived as a mostly southern concern, and giving it the name of a Kansas plaintiff would provide a more national focus.

The Moton plaintiffs also represented the only student-instigated lawsuit that was wrapped into Brown v. Board of Education.

In 1953, Prince Edward County opened a new and improved Moton High School. This one included a cafeteria and gymnasium, although it was still inferior to Farmville High.

But the case was already moving ahead in Washington. And in May of 1954, the Court ruled unanimously that segregation violated the 14th Amendment because “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

Prince Edward County’s Response

But the story doesn’t end there. To avoid integration, Prince Edward County closed all of its schools until 1964. This left 1,700 county schoolchildren at the time of the closures with nowhere to go.

White students who could afford to eventually began attending a new private school—Prince Edward Academy—that at first opened in church basements and other temporary locations. Some kids were sent away to live with relatives so they could attend school. Prince Edward County Christian Association sent some 50 black children to an African Methodist Episcopal junior college in North Carolina. About six dozen black children were rehomed by the Quaker American Friends Service Committee so they could attend schools elsewhere. Other students attended grassroots schools started by some of Moton’s teachers. Finally, volunteers came from other states to work as tutors in the county.

Johns never was able to return to Moton to continue her schooling. Concerned about threats made against her, her family sent her to live with an uncle in Montgomery, Alabama, to finish high school. After attending Spellman College in Atlanta and graduating from Drexel University in Philadelphia, Johns became a librarian, married, and had five children. She died young, at 56, from bone cancer.

Remembering Johns

Today Johns is far less well-known than the civil rights leaders who followed her and who were motivated partly by schools’ failure to integrate after Brown, the case sparked partly by her actions. However, people who live in or visit Virginia are reminded of her courage: The state attorney general’s office building is named the Barbara Johns Building. The Farmville library was dedicated to her. And a statue of Johns stands on the grounds of the state Capitol in Richmond.

The Moton School Strike represented a convergence of people linking different aspects of the Civil Rights Movement. Johns was the niece of Vernon Johns, a prominent civil rights advocate. Moton school was named for Robert Russa Moton, who served as president of the pioneering Tuskegee Institute after Booker T. Washington. The lead attorney for the plaintiffs in Brown v. Board of Education was Thurgood Marshall who, more than a dozen years later, became the first black Supreme Court Justice.

Related stories:

Judy Heumann: Rolling out Rights for the Differently Abled

Fred Korematsu: Standing up for Citizens’ Civil Rights

Read more:

http://www.motonmuseum.org/biography-barbara-rose-johns-powell/

The Forgotten School in Brown v. Board of Education

Overlooked No More: Barbara Johns, Who Defied Segregation in Schools

Massive Resistance in a Small Town

The 16-Year-Old Who Fought Segregation