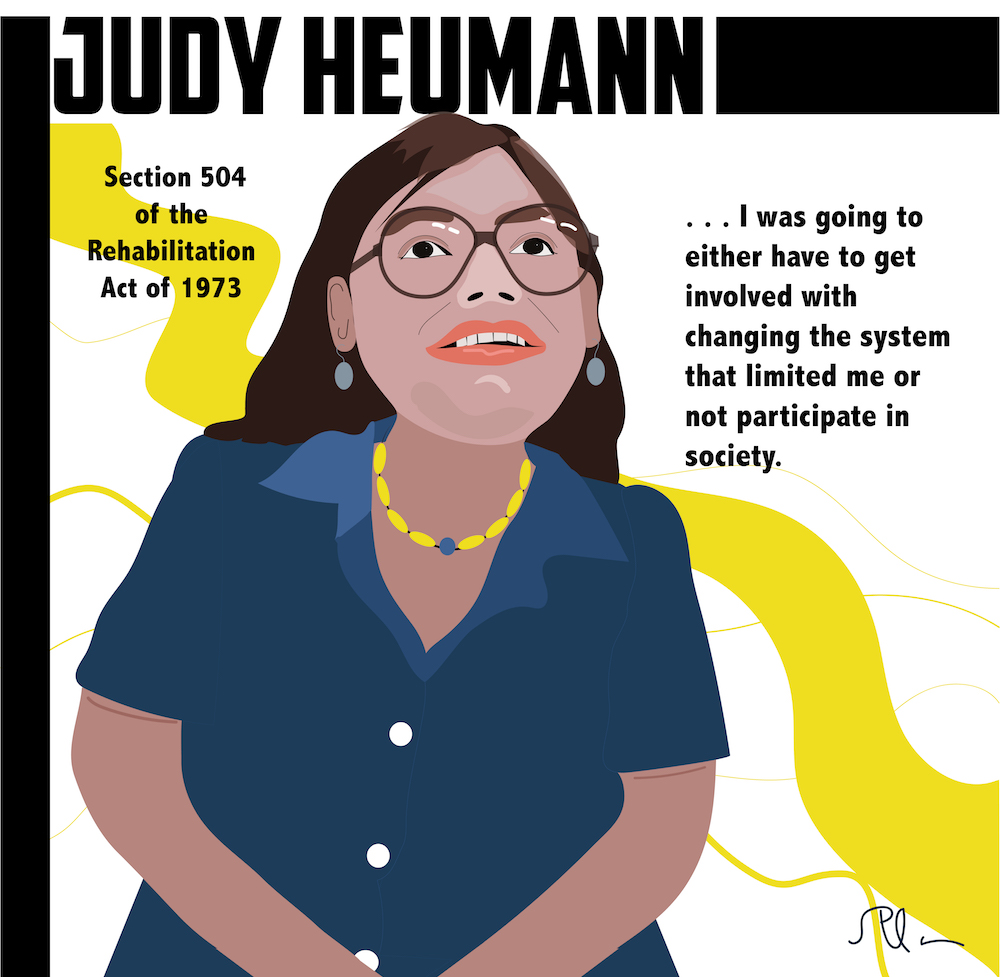

Judy Heumann: Rolling out Rights for the Differently Abled

Imagine that your primary means of locomotion is a wheelchair. Now imagine that between you and the front door of all institutions receiving federal money is a set of stairs or a high stoop. How do you manage? How do you take your kid to school? How do you check out a library book? Get a passport? Vote?

The ramps you see everywhere today to make mobility possible for all citizens weren’t a fixture half a century ago. Just 50 years ago, students with disabilities weren’t guaranteed an equal education. Employers could legally discriminate against people with disabilities. If you were hearing impaired, there was no guarantee you’d get your medical treatment explained to you. The reason conditions are so different today is largely because of the hard work of someone you may have never heard of: Judy Heumann.

Fighting for an Education

Heumann, the daughter of German-Jewish immigrants, was born in 1947. She had polio when she was a toddler. The polio left her unable to rely on her legs for locomotion, and she began using a wheelchair early on. Because the wheelchair was seen as a fire hazard, her public elementary school refused to allow her to attend.

After three years of two hours per week in-home instruction provided by the school for Judy, her mother Ilsa had had enough. She went to bat for her daughter and won her a spot in a school for disabled kids starting in fourth grade, with the understanding that she could complete elementary school and then would return to studying at home.

But when it was time for high school, Ilsa once again fought for her daughter’s right to be educated, and Judy was admitted to the public high school. After graduation, Judy attended Long Island University, which is where she began her career as an activist. While studying speech therapy, she also took time to organize protests aimed at getting the university to improve access for disabled students by adding ramps to make classrooms and dorms accessible.

Heumann v. Board of Education

When Judy graduated, she was eager to start teaching, but the Board of Education of New York determined that, once again, her wheelchair was a fire hazard, and they refused to grant her a teaching license. Undeterred, Judy sued the Board of Education. The Board settled out of court, and Judy became the first New York teacher in a wheelchair.

The renown she earned from her lawsuit turned her into a celebrity among the disabled population, and Judy started getting letters from people all over the country telling her about their struggles with accessibility. In response, Judy and a few disabled friends started a nonprofit, Disabled in Action, dedicated to fighting for the rights of the differently abled.

P.L. 94-142

Judy began working as an aide to Senator Harrison Williams of New Jersey. In the early 1970s, she helped write Williams’s special education legislation, P.L. 94-142, which guarantees a public education to disabled kids. The law passed in 1975.

California, Here I Come

In 1975, Judy relocated to Berkeley at the request of disability rights advocate Ed Roberts to work as the Executive Director of his Center for Independent Living, a groundbreaking residential program for disabled Berkeley students that was part of the early Independent Living Movement. ILM spread the radical notion that the goal for disabled people should be for them to live as independently as possible.

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act

In 1973, the Senate and House enacted Section 504 of The Rehabilitation Act, which guarantees the disabled population freedom from discrimination. Senator Hubert Humphrey initially tried to wrap disability language into an amendment to the 1964 Civil Rights Act. But he was persuaded instead to add the language to the Rehabilitation Act of 1972.

President Nixon vetoed Section 504 two times when it was part of the 1972 Rehabilitation Act, but he finally signed it when it was part of the 1973 legislation, after independent living provisions had been removed. But then the legislation sat around waiting for some teeth. A lawsuit that demanded that regulations be crafted resulted in a judge ruling in the plaintiffs’ favor, but he failed to provide a timeline for the regulations.

Attorneys from the Office for Civil Rights drafted regulations and forwarded them to Joseph Califano, the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW). Califano sent the regulations to Congress, and Congress sent the draft back to Califano. By 1977, Jimmy Carter was President, and under his administration, Califano set up a task force to review the regulations. The task force included no members of the disabled community, and it weakened the drafted regulations.

The American Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities warned the task force that, if HEW did not reinstate the regulations as they had been submitted and sign them into law by April 4, they would take action. The ACCD then planned just-in-case sit-ins at eight different regional HEW offices to take place April 5.

Sign 504 Sit-in

When Califano failed to sign as expected, protestors showed up at the eight offices across the country on April 5. More than 300 people showed up in D.C. and confronted Califano in his office, but he still refused to sign.

But the most effective sit-in was the one organized by Judy and her colleagues Kitty Cone and Mary Jane Owen in San Francisco. After a rally involving some 500 people, about ten dozen disabled activists descended on the HEW office, entered the building, and went upstairs to the office of Director Joseph Maldonado, who reported to Califano in D.C., where the protestors planned to stay until the regulations were signed.

Judy, Cone, and Owen had learned a great deal about organizing protests over the years, and they knew that disabled people would need abled allies to help them occupy a building. They called upon their relationships with a wide range of groups, including the Black Panthers, the Gay Men’s Butterfly Brigade, and the United Farm Workers, and on powerful individuals, including Mayor George Moscone, UFW’s Cesar Chavez, and Senator Alan Cranston.

The Black Panthers brought food to the protestors, and the City provided air mattresses and portable showers. When the D.C. offices of HEW had the phone lines cut, the City installed new ones. Without their caregivers present to help them, the protestors turned to one another for help with medications and activities requiring sight or hearing or physical strength.

The protestors stayed for 26 (some say 28) days until Califano relented and signed the Section 504 regulations. The sit-in organized by Heumann, Cone, and Owens was the longest nonviolent occupation ever of a federal building in the United States.

To find out what Section 504 achieved, read here.

A Career of Fighting for the Disabled

After Section 504, Judy continued fighting for the rights of the disabled. In 1983, she co-founded and served as director of the World Institute on Disability. She was named the first Director for the Department on Disability Services in D.C. In 1993, she became Assistant Secretary of the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services at the U.S. Department of Education. In 2002, she started working for the World Bank Group as their first Advisor on Disability and Development.

In 2010, President Obama appointed her the Special Advisor on Disability Rights for the U.S. State Department. And in 2017, she went to work for the Ford Foundation as a Senior Fellow focusing on issues of disability.

She has been included in documentaries, given a TED talk, and appeared on C-SPAN, and at 73, Judy Heumann shows no signs of slowing down as she continues to forge new paths with her wheelchair.

Featured illustration by splane.

Related Stories:

Barbara Johns: The Teen Who Started a Movement

Fred Korematsu: Standing up for Citizens’ Civil Rights

Read More:

The 1977 Disability Rights Protest That Broke Records and Changed Laws

Drunk History: Judy Heumann Fights for People with Disabilities

Polio Place: Judith E. Heumann

U.S. Department of State: Judith Heumann

Ford Foundation: Changing the Face of Disability in Media

Disability Action Center: Judith Heumann

https://dredf.org/504-sit-in-20th-anniversary/short-history-of-the-504-sit-in/

https://dredf.org/about-us/people/judith-heumann/