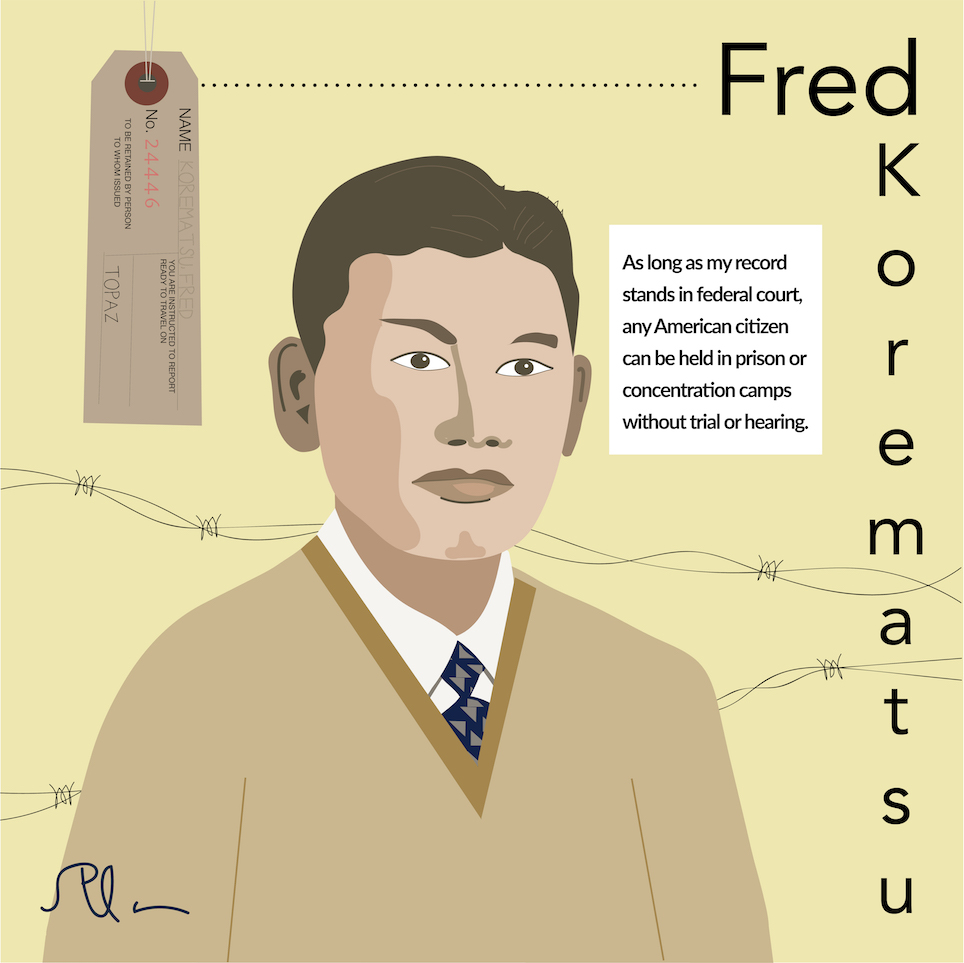

Fred Korematsu: Standing Up for Citizens’ Civil Rights

One day, signs are posted all over your American town saying that all people of your particular ancestry—whatever you are, Irish, Mexican, Somalian, or Swedish—have to get ready to relocate. You need to pack up bedding, utensils, and dishes for everyone in your household. You’re told to pack toiletries and a few changes of clothes. You can bring a few personal items too. But your beloved pets have to stay behind. You have to leave your house and your land, your farm, your business, your vehicles, your furniture and appliances, your friends and neighbors.

You’ll be taken to new housing somewhere far from your home, housing that you’ll discover is Spartan, cold, and surrounded by barbed wire.

That’s exactly what happened in 1942 when President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, forcing the relocation of all Americans of Japanese ancestry to concentration camps. When they were transported away from home, they didn’t know where they were going, what it would be like, or when, if ever, they’d be allowed to return home.

And when they did return, years later, many of them—but not all—found that their things and businesses and property had been repossessed by their former neighbors. Many of the internees no longer had a place that felt like home.

Defying 9066

In 1941, Fred Korematsu, a Japanese American, was only 23. He lived with his parents in Oakland where the family ran a plant nursery. Fred had a girlfriend and a job as a welder at a shipyard. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor at the end of ’41, Fred was laid off.

In February of 1942, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. By March of that year, General John L. DeWitt had issued Proclamation No. 1, which divided the western states into two military areas. DeWitt announced that all people of Japanese ancestry would need to leave Military Area 1, which included Oakland.

Fred didn’t want to go. He didn’t see why he should have to since he was an American. When his family reported, as instructed, to the Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno, a temporary camp set up at a horse racing track that eventually housed more than 7,000 detainees, Fred stayed behind with his Italian-American girlfriend.

That meant he needed to go into hiding. To disguise his appearance, he had minor plastic surgery. But by the end of May, he had been discovered, arrested, and sent to jail at the Presidio in San Francisco.

Taking It to the supreme court

Fred’s case drew the attention of the American Civil Liberties Union, which was looking to challenge the constitutionality of 9066. Fred agreed to join two other relocation resisters in the test case. During the wait for trial, the Executive Director of the ACLU, Ernest Besig, paid Fred’s bail. Fred was immediately sent to Tanforan and then later, with many of the Tanforan internees, to the Central Utah Relocation Center known as Topaz.

In federal district court, Fred argued that there was no reason for him to be sent to a detention camp since he had signed up for the draft and tried to join the Navy to fight in defense of his country. He argued that he had very few ties to Japan and, therefore, could hardly be accused of working for the enemy. He didn’t even speak Japanese well and had never been to Japan.

But Fred was nonetheless found guilty of violating a newly passed law, one that made it illegal to defy a military order of relocation. He was sentenced to five years of probation. In 1944, his case on appeal was bumped up to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court eventually ruled 6 to 3 in support of the federal district court’s decision.

In his dissent to the ruling, Justice Robert Jackson wrote, “The Court for all time has validated the principle of racial discrimination in criminal procedure and of transplanting American citizens.”

Getting out of camp

At Topaz, Fred worked in the warehouse of the camp hospital. But eventually, he was given permission to work outside the barbed wires. He picked beets on farms and later got a job welding in Salt Lake City.

After the war, Fred moved to Detroit where he married and found work as a draftsman. That’s where he was living when the Supreme Court heard his case. He and his wife had children, and in 1949 Fred and his family moved to California.

Reopening the Case

For 30 years, Fred was followed by his felony conviction, which prevented him from advancing much further in his career. But in 1983, a legal historian named Peter Irons and a researcher named Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga uncovered documents that had been kept from the Supreme Court during Fred’s case. The documents showed that there were no incidents of treason committed by Japanese Americans in advance of 9066 and, therefore, the documents supported the idea that 9066 was not necessary for national security.

A team of lawyers from the Asian Law Caucus and other organizations reopened Fred’s case and, by November, the federal court had overturned the 1944 ruling.

Fighting for civil rights

Korematsu was re-energized by the overturning of his conviction, and he threw himself into the work of pushing for the Civil Liberties Act, which Congress finally passed in 1988. The Act provided $20,000 compensation and a federal apology to every person who had been put in the camps as a result of 9066.

Ten years later, President Clinton gave Fred the Presidential Medal of Freedom. But Fred wasn’t done. Just before his death in 2005, he filed a court brief with the Supreme Court on behalf of detainees in Guantánamo.

In California every January 30 is Fred Korematsu Day, a celebration of Civil Liberties and the Constitution.

Featured illustration by splane.

Related Stories:

Barbara Johns: The Teen Who Started a Movement

Judy Heumann: Rolling out Rights for the Differently Abled

Read More:

Fred Korematsu Fought Against Japanese Internment in the Supreme Court… and Lost

Exactly.